Woodplumpton. A small parish five miles away from Preston. Home of a dead ‘witch’ in a churchyard.

Somebody is very cross on Trip Adviser that the pub in Woodplumpton has been categorised as being in Blackpool instead of Preston.

It might also be the only Tripadvisor review of a pub that mentions the grave of a witch along with details of some poor service and disappointing slightly cold chips.

There needs to be more Tripadvisor pub reviews with references to the paranormal along with random pictures and folklore artifacts.

I went there today. The sun was setting, the expensive flowers left on Meg’s grave still fresh.

A long dark shadow suddenly looms over me in the fading twilight.

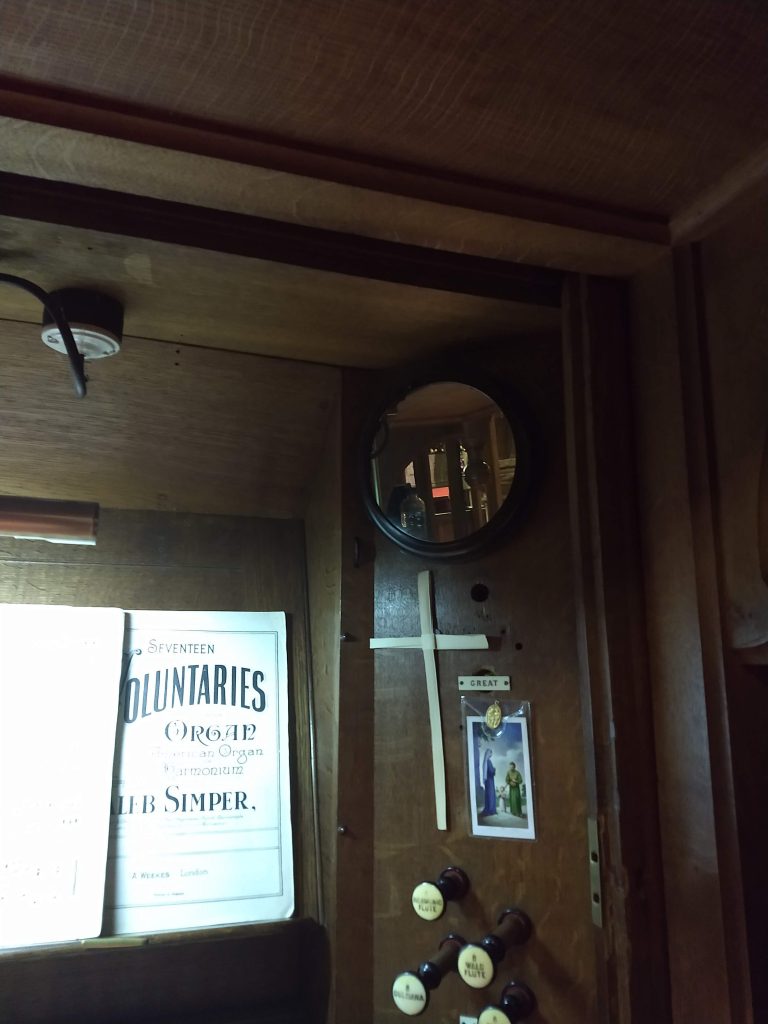

Raymond is an organist from the church, a fellow graveyard lover who also has such exquisite copperplate writing when I ask for his details that I suddenly suspect him to be a ghost from the past.

He tells me much about the grave. Not only are flowers frequently left but jewellry as well.

Meg’s grave unlike others never goes without. He takes me on a tour of the church, it is nearly dark now and what a splendid church, low beamed, some spectacular stained glass windows but such an aura of cosiness, rather than high vaulted cold austerity and glory. Maybe it was Raymond, my friendly beacon through the darkened allegedly haunted church.

And the tales, written about, the old superstitions are still alive; the spitting on the grave is an unpleasant tradition but a tradition still knowable and I was warned against standing on the stone due to the stories of the consequences. History becomes of its own, not just of the old superstitions but seeing the stone, the stone found due to the brightness and beauty of the flowers laid upon it and the pretty decay of previous gifts, small jars slimed with the residual juice of old flowers lying underneath the rounded rough stone, so incongruous in this cemetery of straight lines and neatened trees.

Raymond was well aware of the figure of Meg having been seen in the church. He had never seen her, was happy in the warm sanctity of the church but also told me as we stood in the glow of the sunset that he believed in spirituality.

He respects Meg’s grave and knows it for an important place.

Legends in a digital age

According to legend, local children were told that if they skipped three times around the witches grave singing ‘I don’t believe in witches’, a hand would shoot up and grab them by the ankle. Knowing the cynicism of children, this atavistic legend is suspected to be untrue due to lack of headlines in newspapers reporting members of the undead grabbing kids ankles.

A somewhat more prosaic approach is described by ‘dale doubtfire’ and others in the comments section underneath a BBC Lancashire online article concerning the grave. All manner of terrible yet still unproven deeds in these days of smartphones and sophisticated recording devices are said to unfurl when interfering with the grave from ‘being ‘got’ by her the night after standing on the boulder and turning around three times, spitting on the rock and running around it three times to keep her safely underneath it to the more complex one of visiting the grave at Halloween at full moon, walking around it three times then running to the post-box for the happy result of seeing a ghostly MONK.

Dennis M Skeet describes another complex ritual:

‘ As a child my wife carried out this ritual, handed down by her father who did the same thing when he was a boy some eighty eight years ago: walk around the grave three times and stand on the stone. Look to the North, then East, then South and finally West. Make your wish. Now run round the church three times and if you see the devil through the keyhole of the church door – run like hell! Make of this what you like. I married a Lancashire lass and have visited the grave at Woodplumpton. Seems true enough to me.’

This ritual is also mentioned in Tales of Old Lancashire in the same precise complicated format.

Whether Meg was truly a maleavelent shape-shifting practitioner of the arcane, a thwarted mistress or merely an independent poverty stricken woman trying to live her life in a harsh world, we will probably never know.

But down there, crushed bones forever lie in a gross parody of a Christian burial.

It was only recently written that people in the area still curse Meg Shelton when their milk becomes sour, their cattle lame.

Does she get blamed for flat iPhone batteries or fat faced selfies or is she finally finally dead?

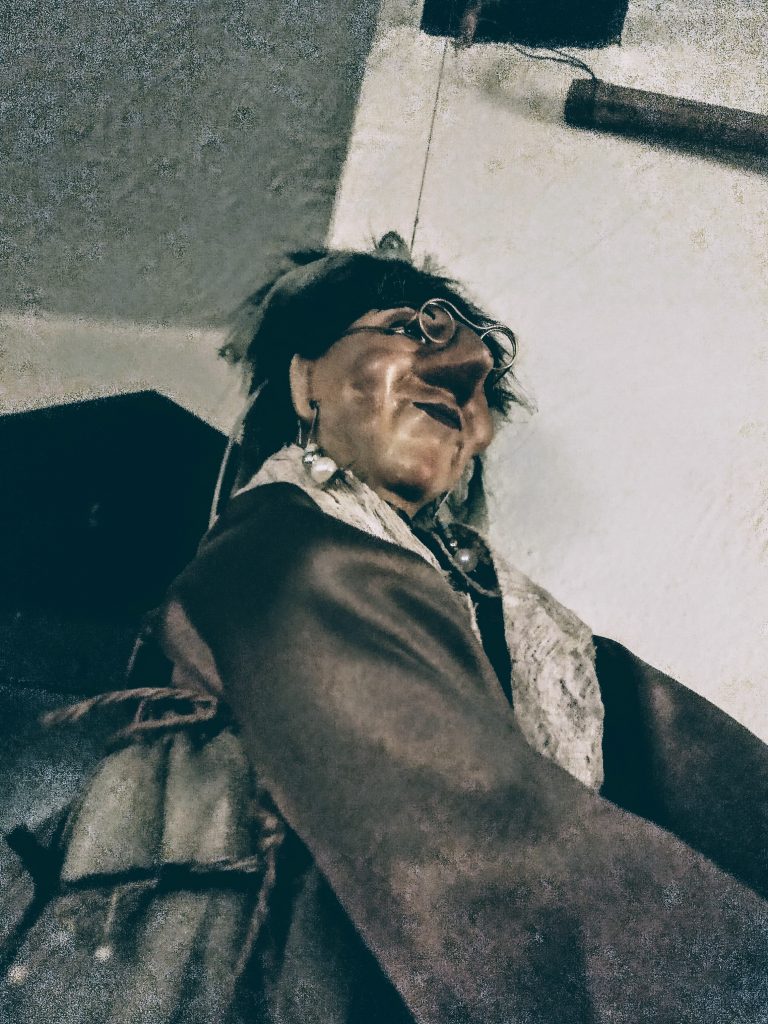

In the 1920’s, a small boy was said to have been left in great distress and terror after being chased around the inside of the church by a wicked looking old lady in old fashioned clothes. This has been attributed to a particularly malevolent cleaner and has been upscaled from previous versions where the child merely only saw an elderly lady in strange clothing.

Another story from the book, Lancashire Ghosts and Legends reports on ‘many people’ seeing her ghost by The Running Pump, an old now extinct local pub. In a successor to the hare legend, her ghost was said to have been struck with a broom and then several minutes later a hare, with a bloody head seen weakly limping across a nearby field.

Also mentioned in Lancashire Ghosts and Legends is an amusing aside detailing a funeral at Woodplumpton church at the beginning of the 20th century. The deceased was over six feet tall and thus his made to measure coffin did not fit on the already dug grave.

‘To the absolute horror of all the good mourners assembled, the sexton who was renowned for his outspoken impatience said ‘Shove t’bugger in end up, same as they did wi’ Old Meg and stand ‘im on ‘is ead!’ ‘

Meg Shilton

A dead witch, so naughty in death as well as in life that despite being in consecrated ground (a privilege the average suicide or unbaptised child was not granted in 1705) she still misbehaved.

This is why we can’t have nice things.

‘By trackless marshes and roadside parishes’, the Fylde was often cut off from the rest of what passed for civilisation in the 17th century. This meant a vicarious reliance on gossip, old customs, prejudices, intrigue and superstition from within an isolated community with a need to dispatch boredom by any means necessary.

Meg Shelton was known as the Fylde Hag, a name she may well not have revelled in. Thrice blessed with names, she was initially known as Margery Hilton and was said to have mostly resided at Cuckoo Hall, which despite its grand name was in truth an isolated cottage near Wesham.

When the story begins, she is at Cuckoo Hall, named as a ‘wretched hovel’ in the Haydock Papers. It would be disappointing if a witch lived anywhere else.

In ‘Goblin Tales of Lancashire,’ she is described as a ‘toothless hook-nosed old woman’.

The text goes on to slightly unfairly relate that ‘perhaps had the ancient dame been somewhat better looking, she might have been borne a different character’.

Superstition and suspicion was rife in the 17th century and every common misfortune was blamed at the hag’s warped door.

Obviously in the late 17th century, a lot of bad stuff happened. Crops failed, milk soured, animals dropped dead or became lame, toes were stubbed, adults died, children even more frequently expired. Siblings were even given the same name whilst both were thriving in the sadly prosaic expectation that one might well be soon to leave this mortal coil and it would be a shame to waste a good family name on a dead child.

Rather than outrageously blaspheming against God, cursing poor animal husbandry, lack of medicine or the unhygienically placed stone water butt, locals were quick to blame witchcraft or more specifically the hag in the hovel.

‘On another occasion she was foiled by a powerful spell, a contrivance by a maiden, whose father suspected his cow had been bewitched. With kindly words, the girl inveigled the unsuspecting hag into her farm and seated her cosily in the ‘ingle neuk.’

Under the ‘squab’ where the witch sat, a bodkin crossed with two weavers healds was laid so Meg once seated was powerless to rise.

‘Oo shonna shift naa fayther, ti’ oo’s t’en oor een oth coo’ said the wench as she heaped turf and wood on the fire till flames roared fiercely up the chimney. The flames grew more and more intense until the unhappy witch was nearly roasted. Her piteous screams drew no compassion until she had removed the enchantment from the cow.’

Translation- Squab-couch. Bodkin- dagger like instrument for drawing ribbons through laces, (often used to prick suspected witches ) Weavers healds – looped wire or cord used for looming.

This archaic ‘spell’ used by normal god-fearing non witches utilising traditional witchcraft tricks, superstition and folklore kept the poor ‘hag’, the Meg Shilton of this chapter, in her place as the farmer’s daughter coldly tells her father not to move as it’s either the witch or the cow.

Cows were very important. Hags less so.

In multifarious shape-shifting old folklore, many stories appear about old Meg such as one regarding a local farmer at nearby Singleton who becomes frequently suspicious as to somebody stealing his corn.

Thus, he carefully counts each bag ( this is a time before Netflix) each night until one night when he notices that he has one sack too many.

He prods them with his pitchfork as only a rural farmer from the past can until one emits a groan.

Lo and behold, it is Meg with a bleeding arm.

Could one say this is less due to enchantment than a woman hiding in a sack after stealing some subsidence for dinner, when hearing the grim plod of a farmer?

If it was indeed witchcraft, it was witchcraft of the most inefficient, banal and unmagical. Hiding in a sack? 2/10. Could you have not done better, Meg with all the powers of Beelzebub at your side?

To be fair to demonic powers, some sources say that she then whooshed off on a broomstick but these seem to have been later more salacious embellishments to credit a slightly worn retold narrative. Were that exciting yet cliched happening to have actually occurred in such a quiet small place, one would have expected slightly more excitement/witch hysteria about the occasion and time and thus transcribed and covered in more detail in local historical records.

Another occasion regarding Meg’s enchanted powers is told in The Haydock Papers where Meg was blithely stealing some milk from cows. She was quietly grazing her goose ( a pastime sadly non existent ) but when a random countryman lout ( it seems they, like witches have always existed) noticed the goose had milk trickling from its beak, he struck it and it smashed into the shards of its previous jug existence.

One would have thought there would be a more efficient Satanic way of obtaining and transporting milk.

It just seems a little… complicated.

In the version in Goblin Tales of Lancashire, she barely escapes with her life after being thrown in a pond ( a link to a witches trial by ducking stool?) by furious locals who presume her closely linked with the devil Himself.

This supposably from a witch so unable to call upon the powers of Lucifer that she was unable to escape from a comfy sofa because of some pins.

A witch who could not just conjure up milk for a cup of tea without a complicated process involving neighbours milk and geese turning into pitchers. Who turned milk sour for no apparent purpose apart from some vague malicious spite, not strong enough to cause mayhem, death and destruction, but just, just enough to make your tea taste a bit unpleasant.

Oh Lord of Satan, deliver us from your evil!

The great hare race

Meg was however so locally regarded as one of those useful utilitarian yet ever so slightly evil witches that the Lord of Cottam, a rich and powerful landowner, just so happened to abide on Meg’s hovel because he could not find any hares to hunt and witches are well known to have strange satanic shape shifting allegiances with secretive elusive hares.

Clever, scared, unknowable Meg thought for a while and aquiensed. She wished no longer to live in Cuckoo Cottage, sneered, feared and loathed. The supposed hunter was the hunted. She needed to escape, a hard task for a poor single lady of a satanic reputation in pretty much any decade and time in existence, even excluding the whole ‘satanic’ bit.

She had heard tell of the landlord, Esquire Haydock having another better more well-appointed hovel, recently vacant in nearby Catforth.

She bartered her supposed gifts for freedom. Of a kind. Meg wanted to live in the relative sanctuary of the aforementioned cottage on the estate of the lord; maybe she feared for her life as a witch in this isolated community and wanted escape and protection from a higher power. If the devil had forsaken her or had indeed had never even been in touch, then a wealthy family of repute might be her saviour against the glances, the whispers, the fear of real violence to come. Even a few miles could mean a small sanctuary.

But only as a witch could she have any bartering tool. Only when presuming to be the monstrous thing everyone hated, could she escape the possible consequences of allegedly being so unnatural.

Thus, to Lord Cottam, Meg agreed to provide a hare to hunt only under the proviso that she could move to the aforementioned squires cottage, a step up from her current lodging and also lodged the appeal that the squire should never release a certain black hunting dog, one with a particularly vicious reputation when she released her own hare.

Shades of Black Shuck, the devil’s own hunting dogs, who appear in old British Folklore, from East Anglia to Devon, ( and across continents too) suddenly loom here.

The Day of the Hunt

Suddenly, as the hounds and the bloodthirsty gentry are waiting, a hare appears, quick and spritely; it breaks through a hedge and bounds off in the direction of Woodplumpton. It almost appears to be teasing the dogs, just as their saliva dripping mouths are about to bring it down, a sudden graceful lolloping in a smooth wide circle to almost back in front of them, a calm brown brightness of the eyes contrasted with the bulbous red stares of its followers.

The chase lasted all day, it was a hard paw and hoof-shattering race but a ‘good’ race for the gentry, their own feet still soft, plump and unsoiled in the stirrups, must end in a win, in blood spilt on soil. A small lithe body ripped apart and grins on puffy florid faces.

The sun was slowly vanishing, the hunters were in fear of being mocked, of returning home without a bloody prize.

The squire forgot or did not care about his promise to the hag, who remembers or wants to remember talking or bartering with such a so-called woman of so little worth?

Blood was up but the light diminishing, the grand ancient trees of the estate turning into a black silhouette. The carefree leap of the hare always just, just ahead making a mockery of them, their positions in life, their drooling, sweating, gleaming eyed expensive dogs.

‘Release the black hound!’

The dog shot from its kennels.

It did not swerve or swoop but ran, ran, ran across familiar hillocks and hummocks, great stretches of heathery boggy wilderness towards its prey. Then was nearly there, nearly about to make that kill, could feel the soft fur against its mouth when the hare suddenly doubled, ran back against itself so quickly as to leave almost a virtual silhouette. The black hound, teeth bared, taut flanks heaving, turned, ran. It was not going to relinquish its prey so easily.

It was dark now, the ancient trees now lost to the night.

The hare however knew the way.

But the dog seemed to know the same, becoming one with its prey. The hare raced, raced, raced, the dog on its heels and the hare ran a familiar trajectory, one known to those who knew the area but who could believe the audacity, the outrage, how something else could know to swerve that patch where the yellow flowers grew, to make a flying leap over such innocent looking flat benign water.

The hare flew, flew, oh how it flew, no limbs moved, just a lithe body in flight, flew towards a cottage, a cottage more renowned as a hovel, a hovel where witchcraft resided. Where Meg Shelton resided.

The hare was nearly there when the maw of the black dog finally reached it. The fetid breath, the steam, the bite.

A stream of blood.

A struggle.

And then, and then. The hare as if suddenly made of mercury made a final desperate leap, the left paw nearly severed but still clumsily clambered, at last losing that vital fluid magic into the hovel of Meg Shelton. Screams were heard from within, more animal than human

And so it was said that Meg Shelton had earned her cottage but from that day on showed a pronounced limp in her left foot.

So it was said.

The afterwards

Meg had well earned her new house. Despite the superstition and hatred of a ‘witch,’ nosiness and gossip holds no boundaries. In a small insular borough, the disappearance of a neighbour is something that people need to be concerned about, or possibly revel in as they eye up the hovel as a ‘needs renovation’ project and gossip furiously.

Some things never change.

So after a while of Meg Shelton not being seen about, either not doing terrible things involving geese, sour milk or just not doing boring mundane things like purchasing ingredients for her pottage, the squire ordered her warped flimsy door to be battered open.

No doubt to a curious crowd of hoverers and gossipers, the door collapsed and within was Meg Shelton’s broken body, slammed betwixt a barrel and a rough wall.

Tragic and suspicious as her lonely fate was, many condemned as a witch died either at the stake or more unofficially at the hands of an angry mob, that one-minded, one brain celled vengeance bound entity that is always to be found somewhere and some time hollering incoherently at a frightened person, no matter the century, time or place.

It is fortunate that by her death in 1710, the witch fever had mostly diminished. There is however the strong possibility that her mysterious lonely death was no accident. Time obscures and the means of her fate is lost. Was it murder or a tragic accident?

Also, why was Meg, known for a witch, buried in consecrated ground? Was it because there were never any charges brought against her apart from the rumours due to the coincidental laming of her foot? Or was it due to the previously mentioned flames of witchcraft hysteria finally simmering down and allowing a lonely member of the parish to be buried respectfully?

Before we get to this, a fascinating hypothesis on the excellent Fylde and Wyre Antiquarian website adds even more colour to the story as to the possible conjecture as to how Meg came to live rent free on Lord Cottam’s land is most salaciously delightful, ergo Meg was utilised as a potential surrogate mother.

It is said that Lady Cottam was infertile so thus maybe the person residing at the interestingly named ‘Cuckoo Cottage’ was connected with ‘heirs’ rather than ‘hares’. At the time, it was common for the lord of the estate to produce an heir by any means necessary. Many stories are told of ‘the cuckoo in the nest’. There are stories of many pubs close to country estates named ‘The Eagle and Child’ such as the one in Bispham Green which tells a story, a familiar story of a wealthy man in need of a male to continue the line but whose wife can sadly not produce such an offspring. However in a delightful twist of fate, a child is found in an eagle’s eyrie, found cooing and grinning and with such a likeness to the lord himself! Fate works such mysterious wonders…and an Eagle and Child pie can be yours for £12.75.

The grave at Woodplumpton Church

Meg now resides at St Anne church in Woodplumpton, a small unassuming church which dates back to the 12th century. Even now many small votive gifts are frequently left on her grave, an unforgotten grave whilst other less legendary far more goodly souls tombs lie forgotten.

The reason her grave is so admired by people who identify with Meg so many centuries later and the reason for her infamy is not in the manner in which she was buried, a moonlit burial, such interments were actually commonplace in the region at the time.

But Meg Shilton came back.

It was a moonlit burial, torches flaring. A black burial on May the second, 1712 for a supposed witch but in consecrated ground. One wonders as to the atmosphere of this sad strange burial of a sad strange woman who died an unnatural death and was like in death buried in darkness and mystery.

It should have ended there.

But it didn’t.

Meg Shelton came back.

Maybe this time, Meg fought back.

People have reported seeing her corpse in the churchyard three times ( a link to traditional tales when things always happen in threes, that strange number of luck and fairytale) although according to one source, three times her leathery hands were found on the top of the grave after futilly clawing their way to the surface. Anyone watched the film ‘Carrie’ ?

Thus her ‘resting’ place was given an exorcism interestingly and suspiciously enough by a priest from Cottam Hall ( a person who might have not normally given his evenings to the graves of random paupers)

It was covered with one of the largest stone boulders in the area in an old ritual of ‘Rock, Paper, Scissors.’ Rocks are strong, rocks are elemental, boulders and graves have links back to the Neolithic period. If you can’t trust an ancient erratic glacial boulder to guard a grave, what can you trust?

This time however, she was said to have been re-interred upside down in a narrow shaft so if she tried to dig her way out, she would be thwarted by her tricks as she was in life.

You can’t trick a witch though.

what a joy to read. enjoyed